|

|

|

|

|

| THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL DAY JANUARY 27 2002 |

| WITNESS TO GENOCIDE Report by John Follain |

| This man was compelled to work in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, slaughtering his fellow Jews. His startling account of the horrors of that Nazi death camp has just come to light |

| He watches as the SS guards, their alsatian dogs barking viciously, order the women who had been stripped of their clothes to enter the gas chamber, where a group of naked men are also awaiting their fate. The camp is usually run with cold efficiency, but someone has underestimated the number of women in this contingent, so a few dozen have to be mixed in with the opposite sex. He sees the surprise on the faces of the male prisoners, and how the surprise turns to anguish as they begin searching among the women to find a wife, a sister, a loved one. One man does find his sister, and they embrace with both relief and embarrassment. A witness until now, Salmen Gradowsky, a Jewish inmate forcibly recruited into the Sonderkommando (special team), the infamous squads ordered by the Nazis to work inside the gas chambers and the crematoriums, steps forward to push the doors of the death chamber closed, and uses a chain to ensure that they are sealed so tightly that not even air can pass through. Later, Gradowsky commits the episode to paper, in a chronicle that has been neglected for decades. It is a first-hand account, written in a Nazi concentration camp, of 16 months in the life and duties of a member of the Sonderkommando - or, as Gradowsky defined it, of 'a guardian of the gates of hell'. |

| It is an account that brings us as close as anyone has come to those chambers without physically entering them. As the Italian survivor Primo Levi wrote in his memoir If This Is a Man, 'We, the survivors, are not the real witnesses. Who has seen Gorgon has not come back to tell the story.' In March 1945, Chaim Wolnermann, a Polish Jew who had survived four years in concentration camps, returned to his birthplace, the village of Oswiecim - or Auschwitz, as it was known to the Germans. They had abandoned it in January, and the 46-year-old Wolnermann drifted from one block to another in the hope of finding a trace, an object that had belonged to a relative, a friend or just an acquaintance. He found nothing, but felt strangely drawn by the piles of false teeth and artificial limbs, the mounds of children's toys and paper bags of women's hair, and the mountains of shoes, many of which had been torn by scavengers seeking hidden treasures. A child was caught splitting a skull with an iron bar to free a gold necklace from a skeleton. |

| Several days into Wolnermann's search, a young Polish peasant came to him and showed him an aluminium canteen he had found while digging among the ashes near the camp's Crematorium III. The peasant was one of the scavengers, exploiting the readiness of surviving Jews to pay good money for any object that would help them keep alive the memory of their lost ones. The canteen contained a notebook covered with elegant handwriting in Lithuanian Yiddish. There was also a letter in the same handwriting, dated September 1944 and addressed to whoever would discover it. Some of the words had been cancelled, or were illegible, and 10 pages of the notebook were missing. But Wolnermann quickly realised this was important, and bought the contents of the box off the young man. We do not know how much he paid, but given the stark conditions at the time, the documents may have cost him no more than a loaf of bread. |

| In the first of the manuscript's 154 pages, Gradowsky appealed to anyone who read his words to contact an uncle at 27 East Brodway (sic), New York, and ask him for a photograph - 'the one of me and my wife' - so that it could be published along with his manuscript. Wolnermann obliged, but it was months before he received an answer. The uncle said he could confirm the documents were in Gradowsky's handwriting, and sent a picture of Gradowsky with his wife, Sonia Sara. |

| When Wolnermann settled in Israel with his wife a year later to work in a kibbutz as a farmer, he did his best to have Gradowsky's wish respected. He showed the manuscript to several publishing houses and newspaper editors, but nobody was interested. The Sonderkommando, the Cains who killed Abel, were taboo. He eventually gave them to the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Israel, where they languished for decades. Frustrated, Wolnermann published 100 copies at his own expense in 1977, but these were destined only for his friends, and one or two also disappeared into the archives of Yad Vashem. |

| Wolnermann died in the mid-1980s and did not live to see the publication in France (last month) and Italy (next month) under the title he had originally suggested: In the Land of Hell. |

| The manuscript has resurfaced thanks to the efforts of Frediano Sessi, an Italian writer and historian, and his colleague Carlo Saletti. Sessi had heard about Gradowsky's manuscript from veterans of the Sonderkommando, and found a photocopy of Wolnermann's edition in the library and documentation centre housed in a building that used to be part of the Auschwitz camp. 'I was surprised to see how easy it was to get a copy,' Sessi recalls. 'Many people had spoken to us about this document, but no one had been able to show us a copy. And it was on my desk very quickly - it was like getting a book out of the local library. It was available for anyone to consult, but no one wanted to.' |

| We know little about Gradowsky. David Sfarad, who met him in the camp as a fellow member of the Sonder-kommando, has described him as 'short and robust, with a round face and cheeks that are a little red, making him seem presumptuous and aggressive'. Born in 1910 in Suwalki, a Polish town on the border with Lithuania, to parents who were small businesspeople, he was very close to his wife's family, who ran a grocery. He worked in his father's business, but he had literary ambitions and wrote short, sentimental stories. He asked Sfarad what he thought of them, and Sfarad recalls: 'I didn't give him too many illusions. His writings were rich in bathos, love for Israel and for Zion, but they were too romantic and too lacking in concrete descriptive images.' Gradowsky would hear his friend out in silence, with a smile that expressed both shyness and irony. Sfarad saw that the criticism did not humiliate Gradowsky, but rather encouraged him to pursue his ambitions. |

| There is certainly no lack of 'concrete descriptive images' in the Auschwitz memoir. 'When I read Gradowsky's account, I see him again before me, as if he was alive,' says Sfarad. 'Each description is a photograph of the inferno which must remain impressed in the minds of people, so that such a crime can never happen again.' Others who have studied the text say it shows Gradowsky was well read not only in Yiddish and Hebrew literature, but also in Polish literature. We know from one of his companions at the camp that few inmates were aware of his chronicle. A prisoner in charge of cleaning the living quarters ensured that Gradowsky was given a bed close to the window, so that he could have more light to write by. |

| We do not know when or how Gradowsky died. Sessi believes he buried his chronicle in the metal box shortly before helping to lead a revolt against the Nazis, the only armed uprising Auschwitz saw. |

| 'Dear reader,' Gradowsky begins, 'you will find in these pages the story of the suffering and torture which wretched creatures were subjected to during their lives in the land of hell that is called Auschwitz-Birkenau.' He adds: 'I think that by now the world knows this inauspicious name well, but no one will be able to really imagine what happened here.' Perhaps, he muses, the reader thinks that what he has heard on the radio or read about is pure propaganda. But not only are those reports, and Gradowsky's manuscript, all true, 'it is a minimal part of what really happened... in this factory of death'. He explains that his aim is to ensure that at least a small part of the truth reaches the rest of the world, so that a vendetta can be carried out. 'I hope that you can thus come to know a reality of immense pain and create for yourself the true image of the way in which the sons of our people were exterminated.' |

| Soon after his arrival at the camp in December 1942 - a journey, he tells us, during which his wife, a gifted singer, led their railway carriage in song - 32-year-old Gradowsky was picked for the Sonderkommando because of his robust, healthy physique. He lost his mother, father, his two sisters, his two brothers, his wife and at least two members of her family. Most of them were burnt to death at the camp 'on December 8, 1942, at 9am'. He has no time to sit down and weep for them, because every day he is drowning in a sea of blood. 'Sometimes I have hoped, I deluded myself that maybe a day will come, a day in which I will be able to have the joy of crying, but who knows...' On March 6, 1944, he writes that the Sonderkommando has been given special orders to prepare for the execution of 5,000 Czech Jews who had been held in the concentration camp for seven months - long enough, the authorities believed, for them to realise what was happening, and to be ready to resist when their turn came. Gradowsky and his 140 companions are given several hours to rest, so that they will be 'in good shape' for when Crematoriums I and II operate at the same time. |

| Two days later, the Czechs are told that they will be transferred to a labour camp, and that they must hand over all their personal effects. Men and women up to the age of 40 are split up according to their trades and jobs, while the others remain with their families and children. The group feels somewhat reassured, and this feeling is heightened when the authorities announce that each must carry his own luggage with him, and will be given some food for the journey. A third trick is played on the prisoners: they are told that the mail will not work until the end of the month, so they should write to their friends now, and use the date March 30, when the military will send on their letters. When the soldiers intervene brutally to separate the men from the women, and start pushing them towards what Gradowsky calls 'a temple where sacrifices are brought to their god to calm his hunger and his thirst with our flesh and our blood', the condemned are confused. So confused that they are unable to understand what is happening, let alone contemplate offering resistance. 'Now morally destroyed, robbed of their strength, it is impossible for them to give birth to a rebellion.' |

| That night, as Jews across the world go to their synagogue to celebrate the feast of Purim, commemorating the salvation of the Jews of ancient Persia, a ritual is about to take place before Gradowsky's eyes. The scene of Crematorium I is floodlit with projectors mounted on lorries. SS guards and soldiers are deployed in battle gear, equipped with guns, grenades and alsatians, and vans loaded with ammunition are parked nearby in case, Gradowsky writes, 'these thousands of victims refuse to fall like flies'. A group of women have finally realised what is about to happen. Gradowsky hears them shout or weep. 'They fall in our arms,' he writes, 'almost fainting and they seem to be telling us, " Dear brother, take my hand and guide me down that brief road that separates us from the end." We brothers who accompany them have our faces lined with icy tears.' |

| The women fire questions at Gradowsky. One wants to know where her husband is, another asks about her brother, another wants to know long it will take for death to come to her. But the soldiers are in a hurry, they threaten the women because they have a job to do, and because they want to spy on their nudity. The women are told to undress, and are told they are to have a shower. And there, some of the prisoners fall not like flies, he says, 'but like women in love (on me and my companions), and in a shy voice they ask us to undress them... Now, on the edge of the abyss, they look only at the superficial things of life and the body, only the body, still feels the impulse to pleasure, and why not offer it the last joy, the one life can still give? They want their young body, full of vitality, to be touched by the hand of a stranger, that he make them tremble and give them the illusion that it is their own lover who caresses them, relieving them of their suffering. The warm lips push towards ours, with love and they try to kiss us'. |

| As he stares at the women's bodies as pale as alabaster, Gradowsky cannot stop himself thinking of how, in a few moments, the faces will turn red, blue or black because of the gas, the hair will be cut off, the teeth will be ripped from their mouths. A woman emerges from the crowd to fetch a silk scarf that lies on the ground. Gradowsky asks her: 'What use is that scarf to you?' She answers: 'It's a souvenir.' Another woman finds the courage to shout at the soldiers: 'Assassins, monsters, criminals! You are about to kill innocent women and children... Now you can do what you want, but the day of vendetta will come!' Moments later, the women begin to sing. First The Internationale, the hymn of the Russian people and their army. |

| Then Hatikva (Hope), the Zionist anthem. And then the Czech national anthem. In the moonlight, Gradowsky sees two men go up to the building where the women are trapped. The men wear masks and carry containers. 'They are tranquil, cold and certain as if they were about to commit a sacred act.' He sees them insert the killer gas into openings in the walls. A big, heavy lid is then placed over each opening. 'In the end the men go away, proud, satisfied, and in the best of moods.' |

| The same scenes are repeated a little later at Crematorium II, where the men are dealt with. 'They too went to their death, without offering any resistance.' There was not enough room in Crematorium I for all the women, so those left over are mixed in with the men, and Gradowsky sees the men, naked, running to see whether their loved one is among the women. Afterwards, it is up to Gradowsky and his companions to unlock the doors of the crematoriums, carry out the bodies, extract the gold teeth, gold earrings and gold rings, often ripped off together with flesh. The bodies are then burnt. Gradowsky notes that it takes 20 minutes to reduce a couple of bodies to next to nothing. |

| For decades the stories of the Sonderkommando were cloaked in silence. In Israel they were regarded as traitors, men who had helped send their brothers to their deaths. It was only in 1974 that their voice was given a wide hearing, when Gitta Sereny interviewed a former member of the squad for her book Into That Darkness. It is likely that the success of that work prompted Wolnermann to publish Gradowsky's manuscript privately. |

| For his classic 1985 film, the nine-hour Shoah, the director Claude Lanzmann interviewed surviving veterans of the Sonderkommando. The film was the first to tackle the mechanics of the extermination - the gas chambers, the crematorium - from the perspective of the men who worked them. But Lanzmann's rehabilitation of them was short-lived. 'People in Israel still consider these people traitors,' Sessi says. 'But they are overlooking the fact that these are young men who were forced to do this work. Some tried to throw themselves into the crema-toriums, or sought death in the gas chamber to avoid doing the work. |

| There's one case, in July 1944, when 400 Jews from Corfu chose to be executed rather than work for the Sonderkommando. These men worked under constant threat of death. There is no justification for the guilty silence of those who for so long robbed them of their voice.' |

| What motivated a man like Gradowsky to write? For Joshua Wigodsky, a member of the Yad Vashem council who has studied the manuscript, it was not a thirst for revenge: 'I don't see a strong appeal for a vendetta, or a desire to see the blood of the enemy spilt, or a desire to kill all Germans. Gradowsky puts himself above all this: he sees in the Jewish tragedy a catastrophe that involves the entire human race.' Wigodsky is surprised that a member of the Sonderkommando not only found the strength to write, but did so with an artistic touch, in his descriptions of the victims, and in the biographies he invents for a particular prisoner, biographies that mirror stories he heard from others in the camp. Gradowsky describes a child and imagines a love story between the child's parents. To a young man he attributes words of love written in letters to his girlfriend. |

| According to Wigodsky, what allowed Gradowsky to write in such a literary style was to a great extent the privileges he enjoyed as a member of the Sonderkommando. The corps was short of neither food nor tobacco, enjoyed periods of rest, and the most devout of them were even allowed to pray, something that was banned for the other inmates. Gradowsky wore winter clothes that had belonged to inmates who had been executed. |

| Again and again, he writes of the fact that the condemned fail to rebel. In 16 months, he witnesses only two rebellions. A young man carrying a knife dares to launch himself at the guards, and manages to stab several of them before being shot dead. A young woman, a ballet dancer from Warsaw, grabs a revolver from an officer and uses it to shoot a senior officer. The other women in her group start beating the SS men, and throwing bottles at them. Other than these, 'the hundreds and thousands, although aware of the truth, went like sheep to sllaughter'. This passiveness shocks him. He is a passionate Zionist, dreaming of the return to the Holy Land, and he is probably preparing his own gesture of rebellion as he writes. In a short section entitled 'Believe', he pledges to defy the camp authorities when they tell him and his companions that they are going to a labour camp. He and his friends are witnesses to the deaths of thousands of people, and will not be fooled. 'Like a wounded beast', he writes, the members of the Sonderkommando will fight back and make their last stand. But, he asks: 'What will happen when we come face to face with the risk that we may lose our lives?' |

| The Sonderkommando did rebel. For weeks, prisoners sent to work in a chemistry laboratory stole firing powder, a pocketful or less at a time. Members stole gold teeth or jewels from the clothes of the dead, and hid them in a crematorium to use as bribes for the guards. On October 7, 1944, the Sonderkommando staged an uprising, armed with molotov cocktails and other weapons. Crematorium IV at Birkenau was blown up, but the rebellion was snuffed out, and more than 400 men were executed, some of whom had escaped and barricaded themselves in a stable a few miles away. |

| It is likely that Gradowsky was killed in that rebellion, or in November 1944, when another 100 members of the Sonderkommando were lined up and shot as the Nazis sought to erase any material and human trace of their crime. Gradowsky could hardly fail to have an intimation of his fate. In the preface to his manuscript, he writes: 'I do not know and I do not believe that I will be able to read these lines when the storm is over. Who knows whether I will have the fortune of revealing to the world the terrible secret which I bear deep in my heart. Who knows whether one day I will live among free men and be able to speak with them. Or whether these lines of mine will be the only testimony to my past life.' |

|

|

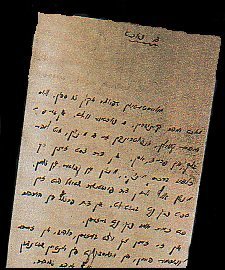

| Above: The hand of a corpse protruding from an incinerator at Auschwitz, after the camp was abandoned by the Nazis. Above right: Salmen Gradowsky, whose long-forgotten memoir reveals the truth about the camp. |

| Right: Gradowsky's manuscript, written between 1942 and 1944 when he worked for the 'special team', or Sonderkommando, at Auschwitz. Above: surviving inmates about to be liberated in 1945. THE STORY THAT WOULD NOT BE BURIED |